Whitfield

Recently, my brother, Keith, and I were reminiscing about Granddaddy Lott, recalling some of the odd and quirky things he used to do. As kids, at least, we thought they were odd. However, we both have had to admit that we are now seeing a large helping of those same quirky, borderline-OCD behaviors show up in our senior-adult-selves. It’s definitely in our genes. I mentioned to Keith how even some of the most mundane things that I now do will remind me of Granddaddy. As an example, I stated how, at mealtime, Granddaddy would let his glass of ice water sit untouched until he’d eaten everything on his plate. Only then he’d take a drink, first a few sips and then the whole glass in several large gulps. I remarked as to how surprised I was when, not long ago, I realized that now I do the same thing.

As we considered other little eccentric habits like that, Keith mentioned that he remembers how Granddaddy once demonstrated—while sitting on the commode, no less—how to fold and refold a sparse length of toilet paper to achieve maximum wiping efficiency while avoiding unnecessary waste. I burst out laughing at this, saying that I also recalled the incident, that I was there at Granddaddy’s house that night, too! As I remember it, Keith and I were both in the bathtub after supper on a school night when Granddaddy came in to check on us. After seeing that we were washing up, he proceeded to give us that impromptu, hands-on lesson in toilet paper conservation while taking care of his own business. Now, that’s an image that will stay with you. I reminded Keith that this was when he and I were staying with Grandma and Granddaddy when Mama had to be hospitalized for six weeks.

That was in the fall of 1960. Keith was 9 and in the 4th grade. I had just turned 7 the week before and was in the 2nd grade. Judy, our older sister, was also staying with us; she was 11 and in the 6th grade. John, our younger brother, age 4, and Karen, our 3-month-old younger sister, were across the field staying with Uncle ’Nell and Aunt Reicey and their four boys.

A lot of that six-week extended stay has been blurred by the decades. Even so, in addition to that vivid bathroom incident, I remember clearly and fondly snatches of many episodes of that long-ago time. I recall how, in the crisp, fall morning air, Judy and Keith and I would walk from Granddaddy’s house up the short sandy lane to the blacktop to wait for the school bus for our ride to Home School. I can still see Wallace, Mike, and Jerry, Uncle ’Nell’s older boys, simultaneously making the same walk up their lane just a hundred yards away. We’d repeat that walk in the afternoon following school. I remember all of us boys playing together and doing chores around both farms in the afternoons and on weekends. I particularly remember working in the chicken barns and in the egg house.

I can still smell Grandma’s kitchen, and how delicious the pies and cookies were that she would bake for our after-school snacks. I also remember how tender and sweet Grandma was when putting me to bed at night. Keith was usually already asleep on the hide-a-bed sofa in the living room when I would crawl in beside him and Grandma would tuck me in. I don’t remember being overly sad at bedtime, but I’m sure I was, and I’m also sure that she was especially sensitive to that fact. I distinctly recall how disconcerting it was to be awakened in the middle of the night by a single chime of the mantle clock in the den, momentarily wondering where I was and not knowing whether it was 12:30 or 1:00 or 1:30. No doubt there were other confusions just below the surface of my awareness.

Daddy would come by in the evening after he and Uncle ’Nell got in from town where they both worked at Star Chevrolet in Wiggins. He would have supper with us most evenings, going next door afterwards to see his younger children for a few minutes before making that lonely one-mile drive home to tend the chores on our farm and get some sleep. On Sundays, he would drive up to the hospital near Jackson to visit Mama. That hospital was the state psychiatric facility in Whitfield operated by the Mississippi Department of Mental Health. She was 33 when she was admitted there for treatment for post-partum depression.

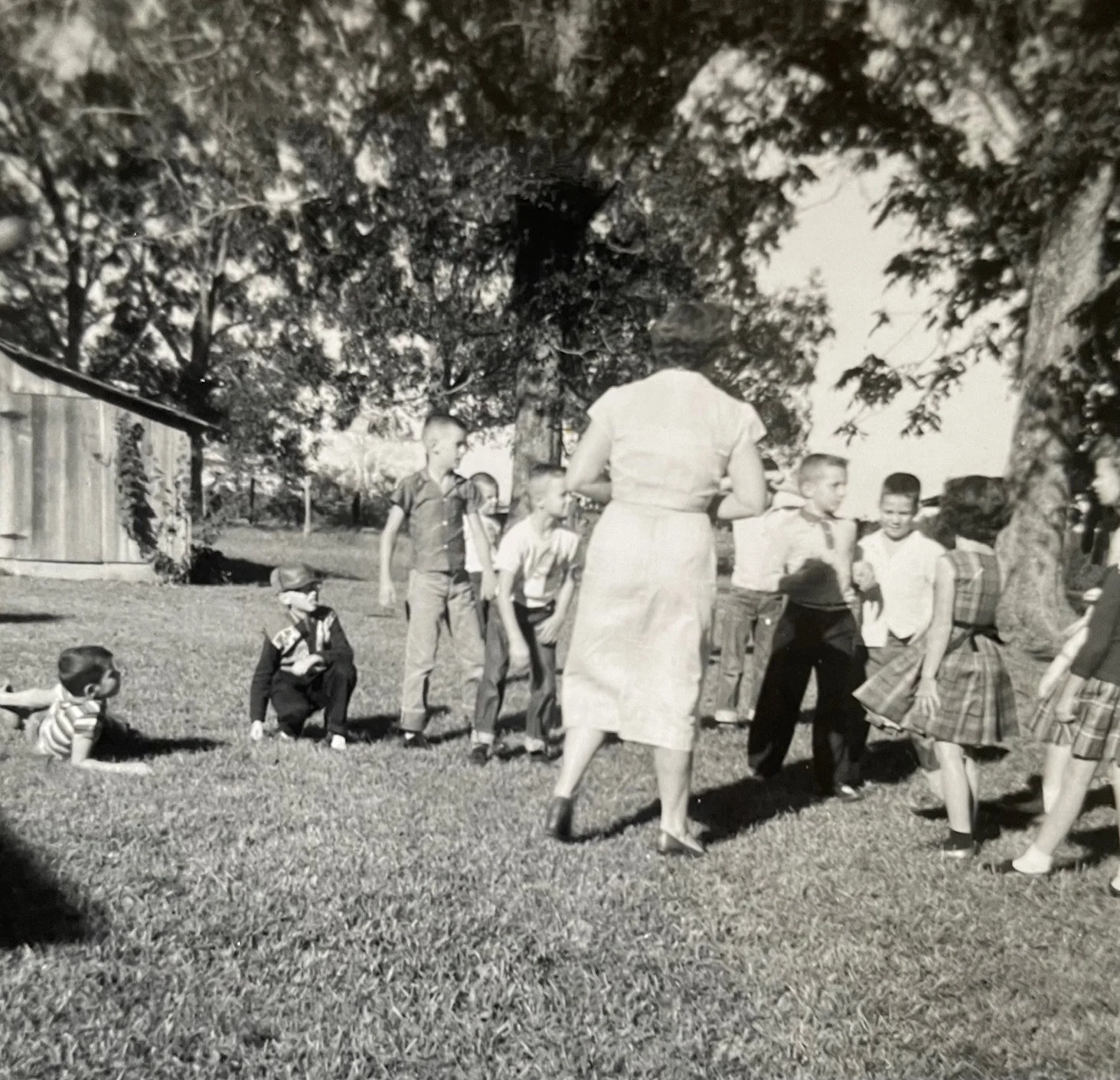

This photo was taken in late October, 1959, on the occasion of my 6th birthday. Mama, being her usual Supermom-self, had invited several kids from the community. In addition to my siblings and cousins, there were approximately 20-25 people there. It was the biggest party I ever had during my boyhood. That’s Mama in the center, leading one of the party games. You can barely see me. I’m the little squirt in the back, left of center, behind the tall boy.

Though I was a bright, somewhat precocious 7-year-old, I honestly had no idea that Mama was sick, nor could I understand why she had to go away, and for so long. It was something that the grownups around me didn’t talk about, not at that time, nor even in the years following. It was only decades later, when Mama wrote of the incident in her memoir, Over the River and Through the Woods, that I learned of the seriousness of the illness and the depth of her suffering. Here are a few passages from her writings:

“It was then I began to exhibit symptoms of depression: loss of appetite, weight loss, sleeplessness, fatigue, and excessive worrying. I was also pregnant with my fifth child, Karen, and trying to be "superwoman" at home and at church. I didn't know how to say "No," and everything anyone asked of me I tried to do and felt guilty if I couldn't...

“A few days before Halloween in the year 1960, I lay huddled against my husband in the back seat of a car heading for Whitfield, the Mississippi State mental hospital, suffering from post-partum depression. It was truly the blackest day of my life. I don't remember who else was in the car, how I got into that car, when we left home, or when we arrived. I remember only the impression that it was night. (I was later told it was daytime.) My thoughts raced through my head much as a tape machine set on “fast-forward,” one idea not completed before another entered my mind, a phenomenon that had been going on for months. My head felt as though a tight band encircled it. I had lived with a debilitating fatigue for about a year. Several months had passed without a peaceful night’s sleep, even throughout the pregnancy. I almost preferred not to sleep, for sleep meant horrible nightmares from which I would awaken screaming and shaking, drenched with perspiration and with heart pounding. Those dreams were far worse than my occasional childhood nightmares. I found out later these were the classic symptoms of deep depression.

“Surprisingly, by that day no tears came. Was this the same too-sensitive young lady whose tears flowed at the slightest provocation? All my life I had cried at the drop of a hat—when I was sad, when I was mad, when I was glad—at the least little thing. Actually, in the preceding months I had run the gamut of emotions, plunging from the highest elation, sometimes hysteria, to the deepest desolation. On that day I was listless, submitting meekly to hospitalization. I had gone willingly, realizing that in my present state I was no good to me or to anyone else. I could not even care for myself; how could I care for my family? I distinctly remember thinking that Reynolds, my dear, loving husband, would be much better off without me and so would my children—especially my beautiful little baby girl, who was only three months old. I was not capable of doing even the smallest tasks in caring for her…

“On that fateful day I never expected to return home; too many people had gone to Whitfield and were never able to return. Those who did, or most of the ones I knew, were institutionalized again and again. Of course, I knew a few who had been cured, but I had no delusions—I would not return. When I was able to leave the hospital in less than six weeks, I was more surprised than anyone else. My memories of those six weeks are fragmented, but the fragments are etched in my mind to this day.

“My first memory was of being in a waiting room with several other patients. Among those in the room was an older lady with white hair named Mrs. Whitfield, who was talking incessantly. Suddenly, I attacked her. In my distorted mind I thought she was the source of all my trouble. Somehow her name being the same as the name of the hospital set me off. I had never tried to hurt anyone since I had quit fighting with my brothers and sisters as a child. Some orderlies from the hospital had to pull me away…

“The next fragmented memory is still illusive. Everything was fuzzy, but I was aware that I was lying on the floor of a padded room, with the knowledge that I had attacked another human being with the intent to harm her. The room contained no furniture. Vaguely, I recall someone bringing food (which I could not eat) and setting it on the floor. I cannot remember being carried there, nor do I know how long I remained in that place. Only that one fuzzy memory remains of lying on the floor with my mind filled with the horror of what I had done. I also recall being in a treatment room, strapped to a narrow table with wires attached to my head. In those days shock treatment was the most common method for treating severe depression. I had heard of it but was not prepared for such a traumatic experience. I knew what was happening to me; it was not painful, but I was scared. I have no idea how often the treatment was administered or for how long.”

Mama wrote just as vividly of some of the other events of her time there, of her various treatments and her eventual recovery. A few of those episodes are hauntingly disturbing and painful for me to read. She tells of being moved into a ward with several other women, most of whom had come from much worse backgrounds and some who had done some terrible things. She also mentioned the kind psychiatrist handling her case and how patient he was and how her improvement came frustratingly slow and gradual. But, eventually she was moved to a private room and was allowed and encouraged to walk freely through the buildings and grounds of the beautiful park-like facility. She recalled how enjoyable it was to receive cards and letters from family and friends back home, and of the occasional visits from Daddy and Uncle ’Nell and Aunt Reicey.

Then as December rolled around, she began to feel like herself again. She writes:

“Gradually, I began to feel more normal, and one day, as I sat alone in a small lounge flipping the pages of a magazine, a picture of a baby caught my attention. For the first time in months, tears began to flow as I thought of my own precious baby girl who I had left in the care of someone else. I couldn't wait to tell my doctor, because I knew then that I was going to be all right. When I did see him, he was thrilled and asked me if I wanted go home for Christmas.”

Within days Mama was released and arrived home two weeks before Christmas. Soon, it was as if she had never been gone. Looking back, all these years later, I still can’t say that I saw any signs of an impending breakdown. There were no cracks in her demeanor, at least none that were evident to me. I guess I was just too young to notice.

Though the odds were against her, she remained emotionally strong, steadfast, and caring, even 18 months later when her 6th child, my baby sister, Linda, was born, and again four years after that, when Daddy unexpectedly died, leaving her with all of us children at home to support.

This photo, from 1954, was taken a few years earlier than the events described above. I chose it for this piece as it represents the strong, happy, and caring person that my mother typically was. I love her radiant smile, her loving countenance, and her obvious pride in her growing family. That’s one-year-old bald-headed me in her arms, with Judy and Keith standing beside us.

Notes:

* Mama stated in her memoir that not long after her stay at Whitfield, she read an article in some national journal that was written by the noted psychiatrist William Claire Menniger, co-founder and director of the famous Menninger Clinic in Topeka, Kansas. Menninger stated that Mississippi was one of only six states in the whole country with state-operated institutions that were successfully treating mental patients and sending them home.

*Over the River and Through the Woods, by Odell Bond Lott, published by Eidson & Associates, Laurel, Mississippi (1995).

A Word to Ponder

quirk (noun): a peculiar, odd, eccentric, and sometimes charming behavioral habit. From Scottish, perhaps from the Low German queer, “oblique, off-center,” which is related to German quer, “perverse, odd”

Source: vocabulary.com

SONG OF THE DAY

“Fire and Rain” by James Taylor (Sweet Baby James, 1970)

James Taylor's iconic song "Fire and Rain" emerged from a period of profound personal struggle. The legendary singer-songwriter penned this deeply emotional track while grappling with clinical depression and bipolar disorder. He spent nine months in a Massachusetts psychiatric hospital at the age of 18 battling these mental health issues.