Old Bob Lott and the Copeland Gang

Have you ever heard of Jesse James and the James Gang? Of course, you have. Those infamous outlaws of the 1870s and ’80s were made household names by virtue of countless dime novels, western movies and TV shows. The very mention of these legendary names, along with the likes of Billy the Kid, Johnny Ringo, Wyatt Earp, and Doc Holliday conjures up images of the old Wild West, of the lawless gunslingers terrorizing cow towns and the upright lawmen charged with protecting the peace back then. Growing up in the 1950s in Big Level, Mississippi, my two brothers and I, like most boys our age, spent many happy hours chasing each other around the yard and up and down our sandy gravel lane at full gallop on our straw-broom horses while wielding our whittled-out pistols and cap guns. We would hide behind pecan trees and under azalea bushes, lying in wait to carry out our murderous attacks on our unsuspecting victims. All of which in our minds was played out in those desert lands and rocky canyons in the western frontiers of Texas, Kansas, and Arizona. Though what I didn’t know as a kid, and only came to realize years later, was that during the early 1800s, just a few years before Jesse James and his contemporaries, Big Level and all of South Mississippi was the western frontier. And it, too, was wild.

Let’s pause here for a brief history lesson. The land forming my boyhood home in Stone County was originally a part of the Choctaw Indian nation. In 1805, the Choctaws signed the Treaty of Mount Dexter ceding their south Mississippi lands to the United States to become a part of the newly-formed Mississippi Territory. When statehood was granted in 1817, there were only two counties in the Mississippi bootheel, the large coastal counties of Hancock and Jackson extending from the gulf coast up to the 31st Parallel. Harrison was carved from the middle of those two counties in 1841, and Stone was created from the top portion of Harrison in 1917.

Before the Civil War, this bootheel area was a vast wilderness covered in virgin pine timber, with very few inhabitants and no significant settlements of any size. At that time, there were no railroads in the interior. This was before the cities of Gulfport and Hattiesburg had been formed. There were only two major roads running through the area that would become Stone County: Wire Road running east and west following the telegraph line from Mobile to New Orleans, and the old City Road cutting across the county from south to north linking Mississippi City on the coast with the area’s only federal land office at Augusta in Perry County. When, in the 1830s and ’40s, the first yeomen farmers began to settle in the area, attracted by the richness of the prime real estate, my ancestors also came: the Lotts, Bonds, Brelands, Hattens and Hickmans, the Batsons and O’Neals, Taylors, Whites and Whittingtons—just to name a few—all of whom I’m related to, either by blood or by marriage. Among these fine, simple, country families there also roamed the occasional band of outlaws. And that leads me back to my story.

Never in our playing of cops and robbers and cowboy outlaws did my brothers and I pretend to be the infamous James Copeland or J. R. S. Pitts, the sheriff who executed him. As youngsters, we’d never heard of the Copeland Gang. I suspect that many of you have not either. This notorious gang of Mississippi outlaws originated in Jackson County in the 1820s, near where Stone County’s southeastern border now lies. For years their thieving and murderous ways terrorized the frontier families living between Mobile and New Orleans and parts farther afield, not ending until Copeland was put to death in a well-attended and well-publicized hanging in 1857 on the banks of the Leaf River at the old town of Augusta in Perry County. While incarcerated in the Augusta jail, Copeland told his life story to Sheriff Pitts who then put it in book form. Pitts' startling narrative of Copeland's notorious life and heyday in crime was published in 1858, a year later. The book created an immediate sensation, recounting in very detailed fashion how Copeland and his gang robbed and looted houses, at times murdering their occupants, how they stole and sold horses and slaves. It describes how one gang member, a preacher, would hold revival meetings during which his partners-in-crime would steal the attendees’ horses.

“Life and Confession of the Noted Outlaw, James Copeland” by J. R. S. Pitts. An online copy is available at Google Books. (Notice that this reprint edition shows the author as Dr. Pitts. Not long after Copeland’s execution, Pitts gave up being a lawman and later became a doctor. He practiced medicine for many years in Waynesboro, Miss.)

Here in South Mississippi, not so many generations ago, his was a household name and the exploits of the Copeland Gang were the fodder of numerous fireside tales as the older folk told and retold stories of the gang’s trail of duplicity, theft, and murder. Not only did James Copeland precede Jesse and Frank James and their compatriots by a generation, Copeland’s nefarious deeds were just as numerous and perhaps even more brazen. So why is Copeland and this fascinating book not more widely known today? It’s a mystery to me.

Several of the folklore accounts of Copeland Gang activity in and about my boyhood home in Big Level and the surrounding area were documented in the WPA Federal Writers’ Project manuscript for Stone County. Among those folk tales are accounts of the gang stopping at several well-known springs to rest and water their horses while enroute from their hideout on the Pearl River down in Hancock County up to Black Creek. Gum Pond, one such watering hole, is near the old Perry Bond place. It is said that Mr. Bond (a relative on my mother’s side of the family) extended his hospitality while unaware of the villainous character of his guests. Another account has them passing by the old Jim Batson place on Red Creek a few miles west of the present-day town of Wiggins. Another tells of the marriage of a Big Level girl to one of the gang’s members. I haven’t yet tracked down this woman’s identity, but it’s claimed that she is buried in one of the county’s older cemeteries.

In case you’re unfamiliar with these depression-era WPA manuscripts, they were written in the late 1930s by the staff of the Folklore Project of the Federal Works Progress Administration. These diverse writers, some beginning authors and others more experienced, were given New Deal employment to gather the life stories and living folklore from the older generation of just about every county in every state in the country. What they produced is a legacy largely hidden today, a historical treasure trove that forms a mosaic portrait of everyday life in 19th- and early 20th-century America. If you’re interested in local history, you owe it to yourself to seek out these valuable works. Okay, now I’m getting off-story again.

Before I discovered the WPA Writers’ Project, the Copeland Gang came to my attention as a result of my genealogy activities. While researching my family tree, I learned that one of my early Mississippi ancestors was robbed and murdered by members of the gang in 1843. That victim was my 4th-great uncle, Robert Lott, one of the sons of my 4th-great-grandfather, John Lott (1740-1808). In the years between 1806 and 1812, before Mississippi’s statehood, the elder Lott and five of his adult sons each received passports signed by the governor of Georgia entitling them to a military escort to cross the Creek Indian lands in their migration to the newly opened-up Mississippi Territory. Shortly after after his arrival in the territory, the patriarch died. However, his sons and their families began to establish homesteads in the Piney Woods. The eldest son, also named John, settled on the Pearl River at what came to be called Lott’s Bluff. Lott’s Bluff grew to become the city of Columbia in Marion County. Another son settled along the Tombigbee River, becoming the progenitor of several prominent Mobile families. One moved on down the Pearl becoming one of the first immigrants to settle Hancock County. And one, my 3rd-great-grandfather, Nathan Lott, homesteaded a place near the Bouie River in what is now Covington County. It was one of his sons that became my first Lott ancestor in Big Level. In addition to being farmers, several of these pioneer men also operated ferries on the rivers and creeks upon which they settled. And, by the way, one son stayed behind in Georgia and was prominent in the founding of Waycross.

Now my story comes back to Robert Lott. This son of John, settled along Black Creek in the eastern part of what is now Lamar County. His home was located where U.S. Highway 98 crosses the creek today, which happens to be just 15 minutes west of where I now reside in Hattiesburg. (A few reading this will recognize that this is where you turn to go to Vesely’s Nursery.) As I stated, Robert was murdered by members of the Copeland Gang during a robbery at his farm. According to a family account, Old Bob, a well-off man, had been out in the barnyard feeding the chickens when he disappeared. Foul play was immediately suspected, as a partial sack of corn was still on the ground. It was soon discovered that the assailants had thrown his body into the creek a short distance away. That spot came to be called the “Bob Lott hole.” Neighbors recovered the body and buried Old Bob on a nearby hill. The murder was reported far and wide, with one account even appearing in the Columbus Georgia Enquirer. The family always suspected that two strangers who had recently been in the area, one claiming to be a preacher, were responsible for the killing. Many thought they were members of the Copeland Gang, but there was no proof.

No proof, that is, until the Copeland book was published 15 years later. In it, James Copeland described the plan to rob and kill Robert Lott and another man, Tom Sumrall, from the nearby Oloh community. Copeland even named the two killers: Gale Wages and John Harden. He stated, “We were all to meet again about the last of February, on Black Creek, at the Pearlington road. We did meet, and a very few days later old Robert Lott was killed and all his money was taken. This was sometime in March, 1844 (sic). Wages was with Harden that night, and helped; I was not there. I met Wages next morning at our camp. He told me what was done and turned me back. Harden and Wages had divided a little over two thousand dollars. Harden left a few nights after for the Mississippi swamp in Louisiana, and Wages and I left for Mobile and traveled altogether in the night to avoid discovery.” [Pitts, J.R.S., “Life and Confession of the Noted Outlaw James Copeland,” University Press of Mississippi (1992), p. 100. On page 72, Copeland is quoted as saying, correctly, that the Lott murder occurred in 1843 and was committed by Harden, who was using the alias John Newton.]

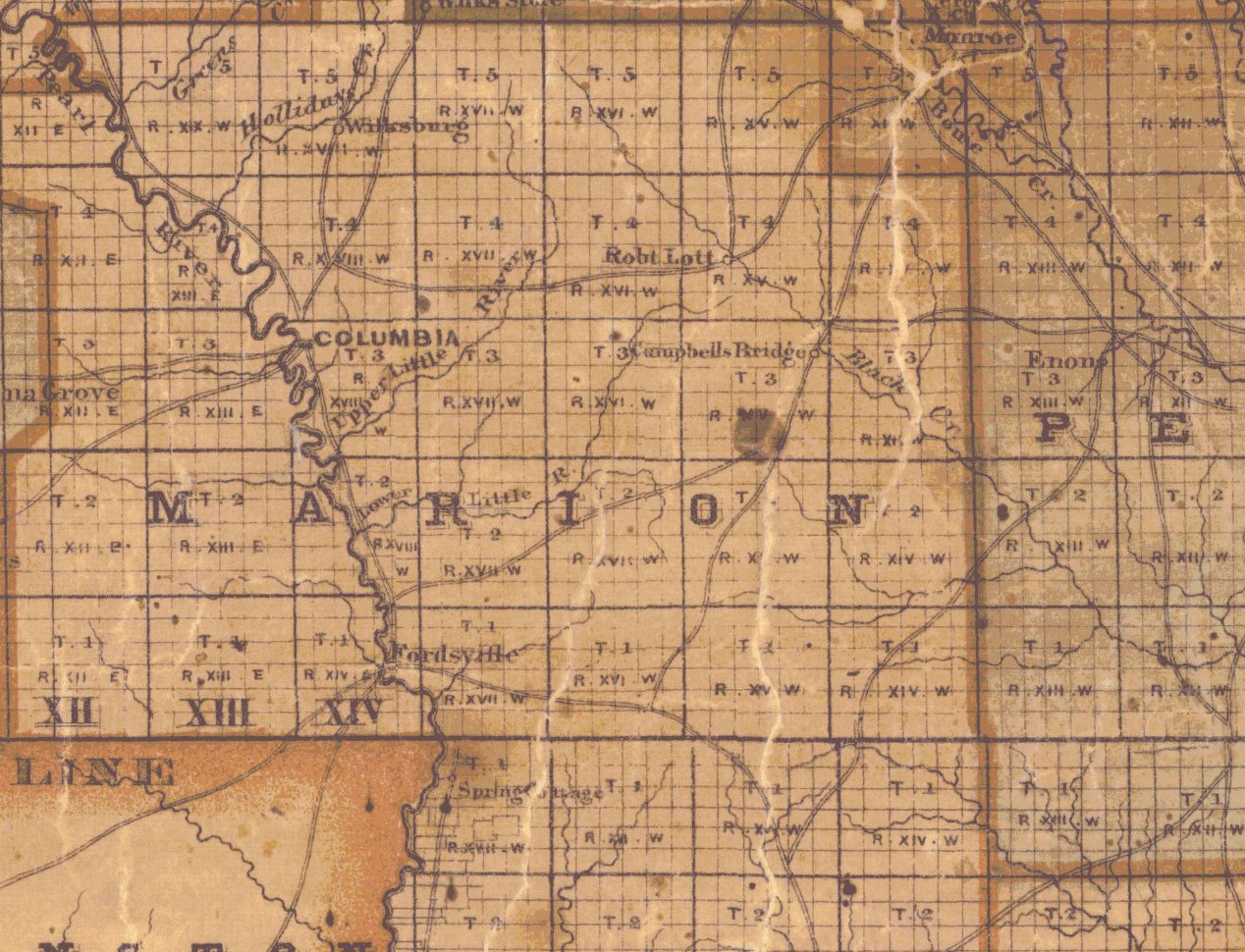

All of these are facts that I have known for 20 years or more. However, a few days ago I made a delightful new discovery when I came across an old map of Mississippi from 1872. I’m familiar with many of the state maps from territorial days to statehood and onward, but this is one I’d not seen before. After reminding myself that 1872 was before many of our present-day South Mississippi cities and towns came into existence—for example, this was before Hattiesburg and Gulfport and there was no Wiggins or New Augusta—I began to look for some of the local towns and communities that sprang up in the early- to mid-1800s but no longer exist. Who among you have heard of Enon and Monroe or Campbell’s Bridge and Fordsville? Well, I hadn’t either. So, imagine my surprise when I saw a little circle indicating “Robt. Lott” on the map. There it was, right there on Black Creek between Columbia to the west and near to where Hattiesburg, a decade later, would be founded eastward on the Bouie River.

“Hardee's Topographic, Historical, and Statistical Official Map of Mississippi” by T. S. Hardee, State Engineer. Published in New Orleans by Hugh Lewis in 1872. The full map can be accessed at the University of Alabama’s online archive of historical maps.

You should be aware that many of the small dots on maps of this era did not signify communities or towns known by those labels, but rather they marked the location of a post office that carried that name. Many of the small rural post offices of that era were located in a corner of the postmaster’s home or store. For example, Big Level did not appear on any of the old maps from around 1900, but the community was indicated by the name of Wisdom, the designation of the post office that my Great-great Uncle Crab Breland operated for many years. I suspect that someone in the Robert Lott family operated a post office in that Black Creek community and named it in honor of Old Bob. That’s something I’ll have to research.

Local history and genealogy! I love it when two of my favorite pastimes dovetail so neatly.

A WORD TO PONDER

yeo·man (noun): Historical: a man holding and cultivating a small landed estate; a freeholder.

Yeoman farmers stood at the center of antebellum southern society, belonging neither to the ranks of elite planters nor of the poor and landless. Most notably from the perspective of the farmers themselves, they were free and independent, unlike slaves and sharecroppers.

wikipedia.com

SONG OF THE DAY

“Funk #49” by the James Gang (The James Gang Rides Again, 1970)

Bonus Track

“Footloose” by Kenny Loggins (Footloose movie soundtrack, 1984)

The chorus of this widely-known Kenny Loggins song flagrantly rips off Joe Walsh’s guitar riff in “Funk #49.” If you’ve never noticed the similarity, give both songs a back-to-back listen. Once you hear it, you can’t unhear it. I’m surprised Old Joe never filed a copyright suit over this overt bit of out-and-out thievery.