“Memories, They Can’t Be Boughten”

A friend of mine recently had a bicycle accident. Fortunately, her only injury was a skinned knee. Looking for something to say, I lamely responded with “Stuff happens, you get better and you’re left with a story to tell.” Trite as that is, it’s quite often the case. But not always, some hurts take a long time to heal, some never do. Sometimes the pain subsides and becomes manageable, only to flare up again at unpredictable times. Some hurts create lasting scars that are painful to talk about for years, even for a lifetime. These are the dark-colored memories that paint the shadows in the canvas of our lives. If I could, I would purchase only the brightly-colored memories, the most pleasant ones available, but it just doesn’t work that way. As John Prine so poetically said, “Memories, they can’t be boughten.” That’s so true. What follows is a story, born out of a painful memory, that I couldn’t tell for a long time. But tell it I must. Like I’ve said before, that’s the burden of memory.

On an afternoon in March of 1967, Daddy and Uncle ’Nell were heading back to work at Star Chevrolet in Wiggins after having lunch at their respective homes in Big Level. These two brothers, close since birth were both master mechanics and Uncle ’Nell was now the service manager. They often shared the four-mile ride to work, going and coming morning, noon, and evening. On this afternoon, instead of going straight back to the shop after lunch, they stopped by Griffin's country store on Hwy 26 to get Cleo Rawls’s car to take it in for service. Uncle ’Nell went on ahead in the company truck while Daddy drove her car. As Dad was entering the city limits, near where the Stone County Hospital is now located, the car left the road on the north side of the highway striking a pine tree head-on. Daddy remained hospitalized for a week and a half before dying from his injuries on the 21st, exactly one month after his 42nd birthday. The cause of this one-car accident remains something of a mystery. There had been a light rain earlier and it has been speculated that the car's worn tires may have been a factor but nothing conclusive was ever established. It was most likely a combination of the tires upon the oily-slick, wet asphalt. But we all know that a momentary lapse of concentration can quickly turn into tragedy. Was it Daddy’s error that caused him to run off the road? I’ve occasionally thought about this possibility, but I decided long ago that I didn’t really want to know.

Though Daddy’s condition was grave—a broken pelvis and various internal injuries—I never doubted that he would be alright. He had survived other serious mishaps and calamities—a collapsed lung while in the Army and his hospitalization just three years before when the wheel balancer at work flew apart and struck him in the face—why wouldn’t he survive this? I desperately wanted to see him, but being 13, and with the hospital’s ICU policies what they were back then, I was not allowed to visit. However, after a few days, almost a week, Mama started coming home at night. This was the tacit assurance I needed that he was improving. We all believed it. Thus, it was an unexpected shock to everyone when he died.

I was at school that Tuesday morning, when Uncle ’Nell and Aunt Reicey came to check out John, Karen, and me. This had never happened before. I could tell by their demeanor that something very odd had happened and had an awful sense of foreboding. Surrogate parents that they were to us, they lovingly shared this sad news to the three of us as soon as we had gotten into the car. They then drove us home where Keith and Judy had just returned from the high school and Mama was already receiving visitors. Linda, only four years old, may have been at home or at Grandma’s—so many details like this I just don’t recall. Even so, I’ll never forget our drive up the lane and seeing 30 or 40 vehicles parked around and in front of our house. It seemed that half the people of Big Level and Wiggins had rushed out to show their respect and to offer their condolences and support. Upon reflection all these years later, it amazes me how rapidly this news had spread in that pre-internet era, and how quickly people had interrupted their workday morning to demonstrate their concern for our family. This outpouring continued throughout that day and later at the funeral home visitation. I still get teary-eyed thinking about it.

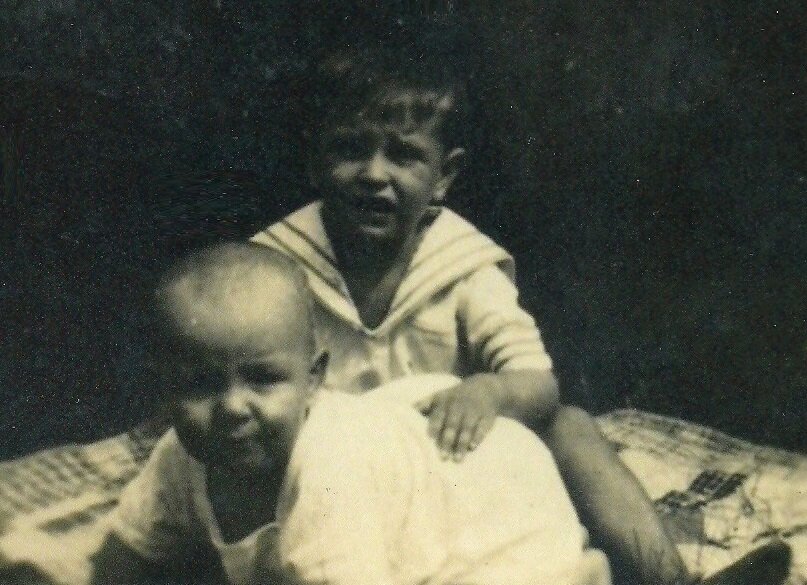

Reynolds Lott, my dad (8 months) and his big brother, Burnell Lott (3), 1925

Reynolds Lott (17) and Burnell Lott (20), 1942.

Dad’s funeral was held at Paramount Baptist Church. It was the first large event in the newly-built sanctuary—the one that he and several other volunteers had spent so many hours helping to construct, the one still in use today. It brought out an overflow crowd. I’ve been present for many other events in that church over the years, revivals, weddings, and other big funerals, but I don’t recall any with a larger attendance. Other than these few mental images, I have only vague, shadowy memories of the days and nights leading up to the funeral and those immediately following, but I do recall the disappointment I felt upon not being allowed to visit him in the hospital. Seeing him at breakfast before getting on the school bus on that last day he left for work already seemed a distant memory. For weeks after his death there were many mornings that I would awaken to discover that this wasn’t just a bad dream and that I had to push through the sadness all over again. I also remember how strong Mama appeared to be. It may have been in part the façade she needed to wear to shelter her family from the immense loss and uncertainty we were all feeling, but I don’t think there was any pretense about it. The strength she exhibited—having just reached her 40th birthday—as she carried herself and the six of us children through those dark days and throughout the months and years that followed remains both an amazement and an abiding comfort.

Reynolds and Odell Lott, 1953, ages 28 & 26 (Daddy and Mama in the year I was born)

Burnell and Loriece Lott, 1952, ages 30 & 29 (Uncle ’Nell and Aunt Reicey).

Going back to school after the funeral was daunting. We had been allowed to stay out for the rest of the week following the funeral—it seemed like a month. I realized I was changed, that I was withdrawn and my personality much more subdued. I had no idea if this despondency would be permanent. I knew I wanted to see all my classmates, but how was I supposed to act around them? How would they act or react to me? Was I to pretend nothing happened? Would they understand the fact that my whole world had been irreparably damaged? Rather than riding the bus that day, Mama drove us to school and checked us in at the office. After getting John and Karen to their classes, Mr. Gordon, our principal, went with me down to the 7th & 8th grade classroom where the morning’s first-period class was already in session. I had an uneasy, awkward feeling walking in after such an extended absence, but Mrs. Bailey, our teacher, quickly welcomed me back and all my classmates beamed as I came in, many shouted my name. Then they began to circle around me, giving me a personal welcome, patting me on the back, shaking my hand, and offering words of sympathy. When it was Sharon’s turn, she put her arms around my neck and pulled me into a sweet embrace that I could not have needed more. All this display of affection and caring did much to begin filling the emptiness and assuaging the strange emotions I was feeling. It was at that point that I sensed I could, one day, actually be okay again.

A Word to Ponder

as·suage (verb): make an unpleasant feeling less intense. From Latin ad- ‘to’ (expressing change) + suavis ‘sweet’; to make sweet.

Source: yourdictionary.com

SONG OF THE DAY

“Souvenirs” by John Prine (Diamonds in the Rough, 1972)